Stardale Updates | June 2025

Honouring Stories, Strength, and Spirit: National Indigenous History Month at Stardale

June marks National Indigenous History Month—a time to honour the deep-rooted histories, enduring cultures, and powerful voices of Indigenous Peoples across Canada. At Stardale Women’s Group, every day is a call to carry forward the stories, strength, and spirit of Indigenous women and girls. But this month, we extend a special invitation to our wider communities: to pause—and truly listen.

To acknowledge this month meaningfully is not just about celebration—it’s about commitment: to learning, unlearning, and taking an active role in breaking generational cycles of trauma and silence.

In this blog, we’ll journey into some of Stardale’s own story—sharing the roots of our iconic drum logo, a symbol tied to our values and vision. We’ll also revisit one of our most powerful historical projects, The Talking Quilt, which wove together stories of resilience, identity, and intergenerational healing.

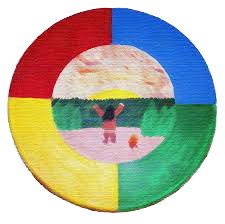

The Sacred Drum: A Story of Art, Healing, and Hope

In the heart of Treaty Six territory, where the North and South Saskatchewan Rivers meet in sacred confluence, a story of healing and artistic awakening began to unfold. It was a story that would touch the lives of countless Indigenous women and girls, carried forward on the painted hide of a drum that would become the beating heart of Stardale.

The Quiet Artist Emerges

Melanie Constant, daughter of Phyllis and Elmer of the James Smith Cree Nation, walked quietly through the doors of Stardale carrying gifts that had long been silenced. Like so many Indigenous women before her, the school system had failed to nurture the creative fire that burned within her spirit. But Creator had other plans.

Through sixteen weeks of the "Honouring Ourselves" program, meeting Monday through Friday from nine till three, Melanie's quiet demeanor began to reveal the artist within. Her hands, guided by ancestral wisdom and natural talent, spoke a language that her voice had not yet found courage to express. In this sacred space of women supporting women, her artistic spirit began to breathe again.

Photo of Melanie Constant and Stardale Executive Director and Founder Helen McPhaden presenting on The Talking Quilt project.

The Talking Quilt and Sacred Teachings

When January snow covered the land in 2000, Melanie returned to Stardale for "The Talking Quilt" program. It was during this time of deep sharing and healing that destiny took shape in the form of a drum—crafted by skilled hands in Saskatoon and destined to become something far greater than its maker could have imagined.

The drum was chosen to become Stardale's logo, its voice ready to carry the organization's message across the territories. But it needed a story painted upon its sacred surface, and there was only one person whose artistic vision could bring that story to life.

Four Directions, Four Colors, One Vision

When asked to paint the drum, Melanie drew upon the teachings of the Four Directions that had been shared in "Honouring Ourselves." She understood that each direction held sacred teachings, protected by the four archangels, and spoke to the wholeness that every Indigenous woman seeks to reclaim.

With reverence and intention, she took up her brushes and began to paint with the sacred colors of Stardale:

Blue for the physical being

Green for the emotional spirit

Yellow for the mental strength

Red for the spiritual connection

Each color represented a gift of spirit, a reminder that healing touches every aspect of our being.

The Painting Speaks

Under Melanie's gentle hands, a powerful image emerged on the drum's surface. At its center stood a young Indigenous woman, her hands raised skyward in prayer and celebration—a gesture of new beginnings and unshakeable hope. Her feet were planted firmly on the land that Melanie knew so well, the territory where the two great rivers meet, surrounded by the ancient forest that had witnessed generations of her people's stories.

This was more than art; this was prophecy painted in living color. The young woman on the drum represented every girl and woman who would find their way to Stardale's programs, seeking hope, belonging, and purpose in a world that had tried to silence their voices.

The Unveiling

May 17, 2000, arrived with spring's promise of renewal. The Aboriginal Healing Foundation grant had made possible this gathering in Melfort, and people traveled from Calgary, Saskatoon, Regina, Prince Albert, and surrounding communities to witness something sacred—the unveiling of the Talking Quilt Project.

When the moment came, Melanie was called forward. In her characteristic humility, this sweet and gentle woman shared the meaning behind her painted vision. Her words, though few, carried the weight of generations and the hope of generations yet to come. The crowd gathered understood they were witnessing something profound—the birth of a symbol that would guide and inspire countless women on their healing journeys.

The Living Legacy

Today, Melanie Constant's painted drum continues to beat with the rhythm of healing at Stardale. It has witnessed thousands of women and girls as they've walked through programs, seeking to reclaim their voices, their power, and their place in the world. Each time they see the young woman with her hands raised to the sky, they see themselves—hopeful, connected to the land, and ready for new beginnings.

The drum serves as a constant reminder that our gifts, no matter how long they've been buried, can still rise and serve the people. Melanie's quiet artistry became a beacon of hope, proving that when we create space for healing, the most beautiful expressions of the human spirit can emerge.

Gratitude Carried Forward

With hearts full of gratitude, we honor Melanie Constant and her sacred contribution to the Stardale community. Her creative energies, channeled through ancestral teachings and personal healing, created something that transcends art—a living symbol of hope that continues to inspire and guide.

The drum she painted reminds us all that healing is possible, that our gifts matter, and that when we raise our hands to the sky, we connect with something greater than ourselves. In the quiet strength of one woman's artistic vision, thousands have found their way home to themselves.

Kinanaskomitin - We are grateful.

This story honors Melanie Constant and all the women who have found healing and hope through Stardale's programs. May the drum continue to beat with the rhythm of renewal for generations to come.

The Talking Quilt: Going Back to the Beginning

This month, to align with the importance of exploring and understanding history, we are diving deep into one of our longest standing projects, The Talking Quilt. The Talking Quilt project merged the therapeutic power of quilting with supportive circle-based healing. Indigenous women found strength as their hands create while their hearts speak. Guided by a residential school survivor, participants discovered the freedom to shed protective armor and embrace wholeness through attentive, non-judgmental listening.

Helen McPhaden's vision, supported by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, brang to light silent suffering through the ancient wisdom of circle work and the transformative power of creative expression.

In addition to the quilt itself, a video was created to document the process both physically as the quilt was assembled as well as emotionally for the participants.

To dive deeper into the archival history of the Talking Quilt, explore our section on news and article publications.

The Healing Quilt: Story from a participant in the project and survivor of residential school.

When we created The Talking Quilt, our vision was to stitch together not just fabric, but stories. Each square of the quilt a reflection of memory, identity, trauma and resilience. For participants, this project came more than a creative outlet; it became a journey of healing and self-discovery through community and togetherness. In the following story, we hear from a participant in the project and survivor of residential school name withheld, whose experience with The Talking Quilt brought to light powerful emotional truths and a journey of true healing. We invite you to read through her words and witness the power and impact of this project.

The Healing Quilt

Copyright: Stardale Women’s Group Inc. 2000

When the Healing Quilt started, I went for the first day and quit. I quit, because it was too hard, emotionally. I knew I had to bring out my feelings, past hurts that were buried deep inside my heart. I went home after the first day, I was shaking and had tears, but I wouldn’t cry.

When I first heard of the Healing Quilt, I eagerly signed up, thinking a bunch of women getting together, talking, laughing while sewing, I went to classes with other women who had similar experiences, feeling uncertain, but excited. I knew we were going to talk about Residential School. I didn't know it was going to be hard on me emotionally, at the end of classes, coming back home, I was shaking and had tears, but I wouldn't let my tears fall. I knew if I cried I wouldn't be able to stop. I was glad I was the only one in the back seat. It gave me time to repair my invisible wall. As soon as I was dropped me off, I told them, "I quit, I'm not going back", and went inside the house. My brother, his wife and sisters, were drinking, I asked if I could have one, then another, after my second beer, we ran out. They went home. I'm sitting down thinking and I started laughing. Here I was trying to forget by drowning my sorrow and we ran out of beer. I know now it wasn't meant to be. I didn't go back for a few weeks. Instead, I went back to my habit (weed); I like pot better than beer, until the teacher asked a fellow participant "to get in touch with her". I've been here doing the Healing Quilt".

The beginning of the class, we talk about what we did for the rest of the week. Then we all go into the quilting room to do a lot of crying and laughing.

The Residential School years: (what we remember).

When you first get off the bus, you are happy, thinking your bus ride is thrilling. Its' your first ride on a bus or for some of us, the first time you rode on a vehicle, halfway, you begin to get motion sickness, by the time you get to the residence, you can barely walk. The building is huge. That's when you start to go into hiding or building an invisible wall. You are separated from your brothers and sisters. You are afraid, but don't cry. Your learn pretty fast, you don't cry because the girl in front was getting slapped around for wanting to be with her siblings. You walk up stairs upon stairs until you reach your dorm. You are assigned a bed until you go home. They give us numbers, you are to remember your number or face another licking. Most of us know our own language, we can't speak English, if you spoke your native tongue, you got hit or faced the strap. The strap is long, brown and black, thick (about 1/4 in.) and hurts like your hand, or other parts of your body, are on fire. You learn to speak English, and push your culture and language behind you. The girls with long hair got it cut short, it takes a lot of years to grow your hair that length. Another part of the punishment was to wash was to wash all the stairs, or wash the shower room. You were given: 2 undervests, 2 panties, 2 socks, 2 shirts, 2 pants, 2 P. J's, 2 bathtowels, 2 facecloths. 1 white shirt, 1 red and black pleated shirt, 1 long knee high socks, black and white oxfords, black tie, and the most hideous red blazer, that you will remember for the rest of your life, this outfit was for church. The church service was long. Some students fainted; we were made to kneel for a long time. If you were falling asleep, a man with a long pole will poke you until you were awake. It was his job to look out for students that were about to fall asleep, or who were asleep, he'd carry the girls with their skirt open facing the boys. We all took a shower together. The showers were in one huge room with ten showerheads. We would wash up fast; we were on a time limit. There were six toilets, a bathtub, a fountain, it was round with a pedal at the bottom, it was where we washed up and brushed our teeth in the mornings, that was on the second floor. Juniors were on the first floor. Intermediates were on the second floor, along with the infirmary, that was our little hospital. If you were really sick, they would take you to the town's hospital. I remember going into the hospital, you had a room to yourself and you were to stay in bed, you weren't allowed to roam the hospital. (I wonder how come!) When you can hear people on the other side talking, laughing and walking around, you didn't mind. You enjoyed being by yourself without 40, 50 or 60 girls around.

The seniors dorm was split in two with the TV room in the back, it was on the third floor. On the main floor were offices and the canteen. Students with money were allowed to spend 25 cents, if their parents sent them money. They were not allowed to keep the cash, the supervisor kept track of that. 25 cents sure got you a lot of candy. 15 cents - bottle of pop, 10 cents - chips, Mojo's - 2 for 1 cent, pixie sticks - 2 for 1 cent. The principal's office was across from the canteen. I remember a strap in his desk; he kept it in one of the drawers. He would pull your pants and panties down, put you across his knee and hit you with the strap. You couldn't sit very well after that. Downstairs was the playroom with wire on the windows. The windows, you couldn't see out or in, unless the window was open. The dining room and the kitchen were downstairs as well. If you didn't like what was put in front of you, you were force fed until it was all gone, even though you puked it out. They would still feed you.

The senior girls were allowed to smoke, if your parents gave you permission. You can smoke outside.

I remember being a little girl and our supervisor. She would come to my bed and spread out my hair around my head, like a halo and said I looked like an angel. I remember being in her room, standing there, at the inside of her room.

That is all I can remember. I don't want to remember.

For snacks before bedtime, they would give us a biscuit about 3in. X 3 in. We called they dog biscuits, they tasted like teething biscuits.

I'm hurting; my head feels like I have a very bad migraine. I'm cold every time I remember and write it down. I can't seem to warm up until I finish writing it down.

Some of us lost a son or daughter, nothing will be able to fill that hole in your heart. The hole will get smaller and smaller, over the years, but will never be completely closed. I thought of suicide a number of times. My boyfriend would make sure someone was with me at all times, even when he went to work. I would like to thank him. "THANK YOU" for being understanding that I was in a depression. After awhile, he would remind me of my miscarriage, just looking at him would remind me of losing our baby. I left him because it was hard on me. As the years passed, I realized I let go of a good man and it was drugs that I was taking that killed my baby. How you lose a baby makes the pain hard, it’s how we cope when a loved one is gone.

Some of us were molested when we were girls, by a close relative or a friend of your relative. We have to realize it is not our fault, or the shame that comes with being molested. I don't know how come they did this to me. It has affected my personality. I have had a hard time trusting people, even my relatives. There are some things I don't tell. Those are mine to beat myself with. My self-esteem is not very high. Since coming to Stardale, I have learned to deal with my problems, which in turn gives me self-esteem, knowing I don't have to hide from myself anymore, but a lifetime of not remembering, is just "being" nothing more or less. Sometimes, old habits come back. It's hard work when you are on a Healing Journey.

My invisible wall is not as solid as before. There are cracks in it that are widening. With each widening, you see a little more of myself, and the world.

Copyright: Stardale Women’s Group Inc. 2000

From the Archives: Healing Words - Volume 2 Number 3 SPRING 2001 A Publication of the Aboriginal Healing Foundation

In spring 2001 the Aboriginal Healing Foundation published a beautiful highlight of Stardale Women’s Group in their Healing Words Publication.